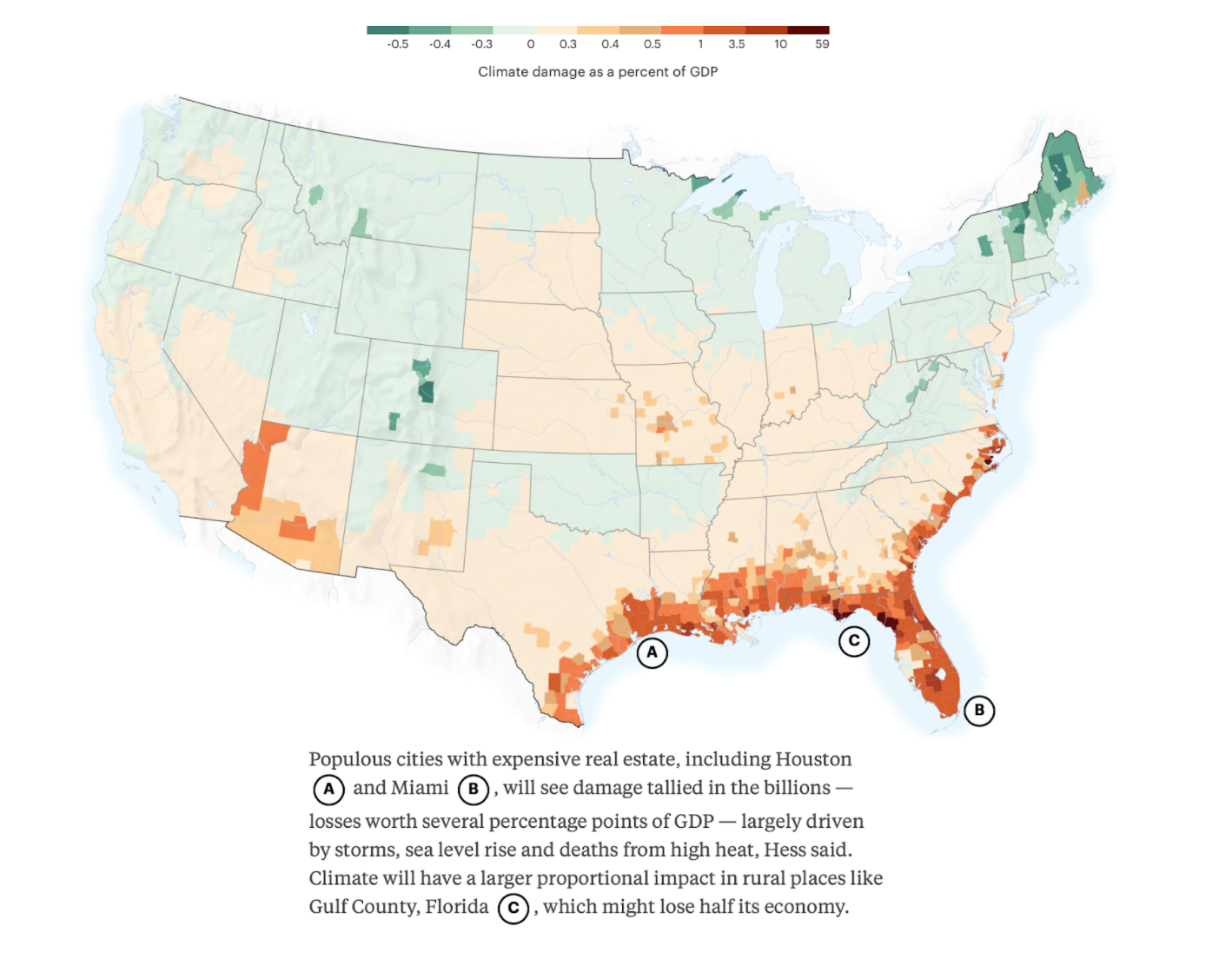

The increasingly severe climate crisis is going to have significant impacts on society. Recent work published by ProPublica shows that, for the United States, the climate crisis will have profound effects on where humans can live and farm. The map below, from ProPublica, shows economic damage between 2040 and 2060 at a county level for the US under a high emissions scenario. The damage is a function of rising energy costs, sea level rise, increased storm and wildfire activity, and changes in agricultural production.

In Lloyd’s recently released Environmental, Social and Governance Report 2020, the Corporation made several commitments in respect of the climate crisis:

- Managing agents are asked to provide no new insurance cover for thermal coal-fired power plants, thermal coal mines, oil sands, or new Arctic energy exploration from 1/1/2022. Existing cover for these risks is expected to be phased out by 1/1/2030

- Investments in thermal coal-fired power plants, thermal coal mines, oil sands, or new Arctic energy exploration will be ended

- Development of a new risk center to research new insurance products targeted at systemic risks, such as climate risk.

While some participants in the market may feel that the Corporation is treading on their toes by making these commitments, Lloyd’s is simply implementing policy set by national governments as set out in the 2015 Paris Agreement.

Lloyd’s commitment to research how new products can be useful tools to address the climate crisis is welcome and helps to future proof the industry - as the climate crisis evolves many risks will become effectively uninsurable, representing a loss of business to the insurance industry.

As a thought experiment, and in response to a line in Kim Stanley Robinson’s The Ministry for the Future[1], we tried to imagine what we could do to evolve the insurance products we have already in a way which would build resiliency into society and start to help address the climate crisis.

Insurance is possibly the most complex of financial instruments as it tries to legally codify what is essentially a promise: if the insured suffers an injury or loss, the insurer promises to make it right, in the shape of a payment. Insurers generally put few restrictions on how that payment is used so long as the injury is rectified. What would happen if insurers started placing stricter requirements on how payments were used?

As an example, imagine adding two clauses to a homeowners’ policy:

- A Resilience Clause: if an insured is located in a high risk area (think flood zone, area of increased wildfire risk, etc) then, post-event the insurance payment could only be used to build back in a lower risk area.

- A Sustainability Clause: regardless of where an insured is located, post-event the insurance payment could only be used to rebuild in a sustainable way (integrated solar power, geothermal power, recycled materials, etc)

The Resilience clause starts to de-risk not only the insurer’s book of business, but also society in general by removing people from harm’s way. One might argue that, purely for the sake of solvency, this is exactly the sort of thing that the US FEMA flood policies should contain given the increasingly unsustainable nature of recurring flood claims.

The Sustainability clause does also, more softly, increase resilience to society (creating a more resilient, clean energy grid) but also allows the insurance industry to put its money where its mouth is; sustainably rebuilt homes will likely carry higher claims costs but reduce, and even start to reverse, the carbon load.

The idea of strict indemnity in an insurance policy has been broken over the years, especially with new-for-old policies; this concept could be considered resilient & sustainable-for-old. Now, we recognize that these clauses come with a financial cost (higher premiums) and a potential business cost (some insureds will object to these clauses and seek insurance without them), and they may even have a social impact (by potentially eradicating communities and possibly impacting the location of urbanisation clusters). So, the questions become, can the policies with these clauses be subsidized (by the insurers, reinsurers, or government) and can the insureds be educated that these are worth having?

On a separate topic, a recent article from Swiss Re noted that a need to reevaluate the models of hurricane risk used by the re/insurance industry in the context of climate change. Swiss Re argues that current models of hurricane risk systematically underestimate hurricane probabilities. The reason for this, Swiss Re contends, is that the past is becoming an increasingly poor predictor of the future and that models based on historical data are increasingly divorced from the reality of the present. To quote the article: “Not only picking the right observation window of past records, but also implementing forward-looking model perspectives becomes paramount.” We welcome this thinking and have long argued that models of risk should incorporate historical data, counterfactual data, and forward looking data to more completely encapsulate the view of risk.

[1] “Lack of predictability means re-insurance companies simply refusing to cover environmental catastrophes, they way they don’t insure war or political unrest etc. So, end of insurance, basically. Everyone hanging out there uninsured.” p54, The Ministry for the Future, Kim Stanley Robinson, Orbit/Hachette Book Group, October 2020.