A Primer on Cyber Security Operations

Many organizations have high turnover, burn out, and incident response challenges in security operations. Lasting and effective solutions are hard to come by. Anyone who has worked in cyber operations, risk management, or even those impacted by a cyber breach has to wonder why.

Why is the current ability to defend computer networks so poor? What is the visibility into our business operations risks associated with incomplete data and underfunded operations? Why do the skills and people gaps remain, even in a highly paid industry?

At QOMPLX, we have been delving into many complex operational decision-making problems from decades of experience across different areas with overlapping risk challenges in cyber, insurance, and trading. Our goal was not to just make better tools, but to actually simplify and navigate unavoidable complexity found in these high-risk industries and apply best practices gleaned from across our different areas of expertise.

From this standpoint we will highlight some common cybersecurity operations challenges like Active Directory compromises. As we share more about our approach to risk at QOMPLX, we will review multiple concepts, discuss solutions and their gaps, and outline some our current QOMPLX people, process, platform, and place philosophies.

Across multiple blog posts in this series, we will discuss how these philosophies can be applied to any Security Operations Center (SOC), Global Security Operations Center (GSOC), or broader cyber-physical fusion operations center. We believe in data fusion because multiple vantage points are required to gain appropriate visibility in support of robust risk management.

Strong operations are a keystone for any business. The modern fusion-enabled ops center is a critical part of enabling sound tactical decisions to become actions and support the strategic goals of the company to achieve long term success.

Before we get too deep into a discussion of operations and risks, it is important to establish a baseline set of definitions. At QOMPLX we always work to have a robust and consistent set of terms – even full formal ontologies or taxonomies – for our work. If you want to dive into more of why we believe this is important for cybersecurity risk, Dan Geer and Jason Crabtree’s USENIX paper is a good start (https://www.usenix.org/publications/login/winter2019/geer).

Here we begin by defining and providing initial references for many of the concepts that we bring up throughout the remainder of this blog series. To this point, a high-level description of what we mean when talking about cybersecurity, operations, defense, offense, and intelligence is covered herein.

Cybersecurity Operations

Interestingly enough, if you search for cybersecurity operations (cyber ops) on Wikipedia you will be redirected to the page Cyberwarfare. There are several reasons for this. First, few terms in this area have widely adapted definitions. Second, many of the substantial primary research and development efforts of these technologies, processes, and training have historically come from government-sponsored and groups with equivalent resources. Many organizations say they do cybersecurity operations, but in fact, many have just a subset of capabilities. This is often due to legal reasons, resource limitations, and/or competing business objectives. While private initiatives, especially in financial services, cloud service providers and select major enterprises in other verticals, are becoming increasingly sophisticated we still have a lot of interplay between intelligence and defense spawned technologies, terminologies, and techniques today.

A simple starting point is to review the common key components for the three key areas for cyber ops: Defense, Intelligence, and Offense. Any good security program will have many of these elements but rarely do organizations have all covered in a comprehensive internal program. Even in cases where a global organization has all these elements they often struggle with building and maintaining a holistic coherent approach due to complexity and interdependence. This is particularly true when moving to accurately understand the business processes of the supported organization and map them to the dependencies in the supporting information technology infrastructure.

At a very high level, let's look at what elements cyber ops covers in defense, intelligence, and offense:

Offense

Cyber offense is often the most visible part of cyber ops. It certainly receives the vast majority of popular press coverage and drives much of the interest from new entrants to the field. Pen-testing, red teams, and vulnerability teams all have a role in many organizations, but are not always properly incorporated. In a military capacity, offensive cyber operations can have separate missions to impact network-connected targets and/or support physical operations through cyber operations to manipulate, damage, or degrade controls systems ultimately impacting the physical world. In a business organization, the offensive cyber teams should have the ability to collect and test the organization to support Intel and defense groups of that organization.

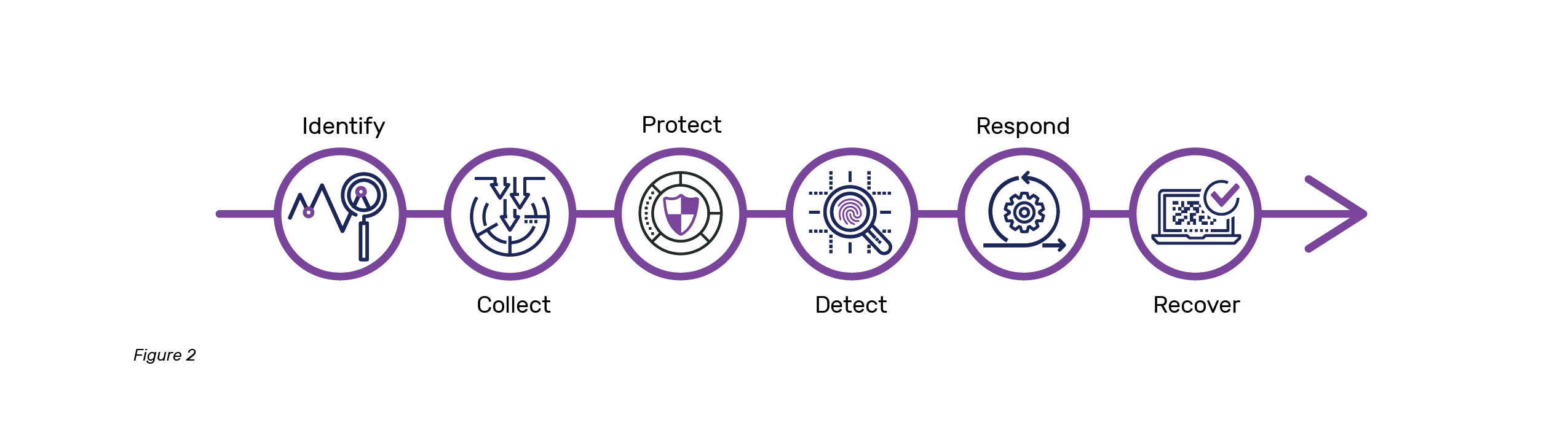

Offensive teams that constantly review their own environments should support identification of new systems, identify potential vulnerabilities, support change management checks, weaponize and deliver attacks to new systems/architectures to test resilience, test detection and response tools, attempt to exploit and control key systems to ensure security, and provide all of this information to key stakeholders for action and remediation. It’s important that offensive efforts are carefully scoped and help provide identification of assets and network topologies, validation of sensor observability and controls effectiveness, exercise links between defenders and the core (usually CIO-led) IT organization, and ultimately help organizations right size their defensive efforts via disciplined threat modeling. The Netflix tool Chaos Monkey is a great real-world example for some of these concepts.

Defense

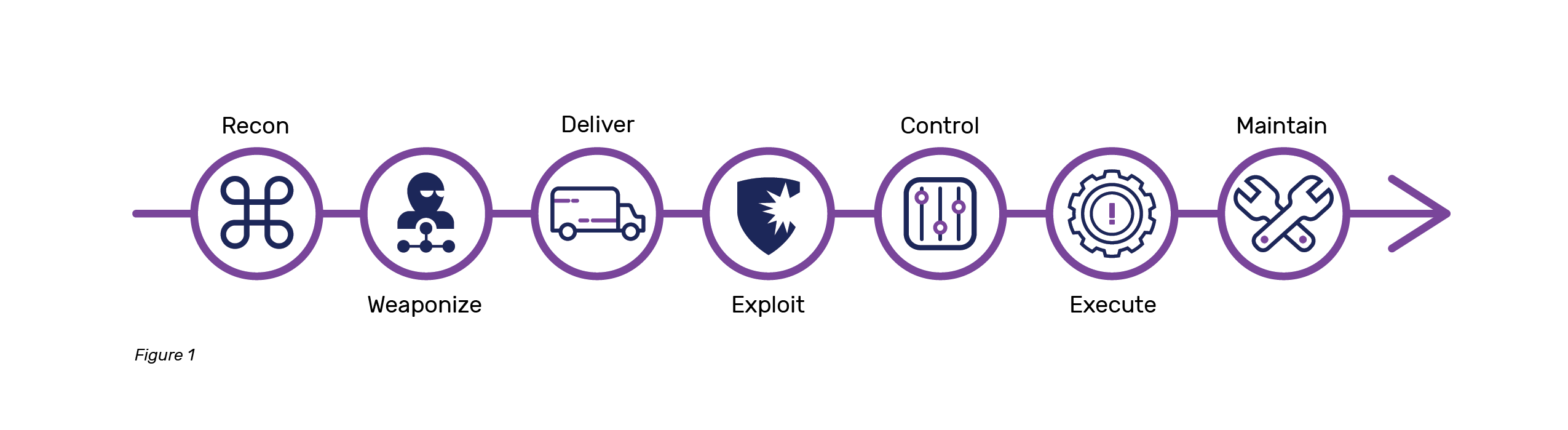

In the digital or physical world, it is often harder to build, protect, and maintain systems than it is to attack, impede, damage, or destroy them. A good defense relies on many things to succeed, and often when done successfully no one will notice what your defense has achieved. Defense is commonly only noticed or appreciated when it fails and visible impacts to the business occur. As the saying goes, defenders must be right every time during every attack, attackers only need to be right once. Unfortunately, lack of resources, visibility, and/or, understanding usually force organizations to focus on a subset of defense areas versus a holistic strategy. The Cyber Defense Lifecycle below (Figure 2) is a high level to outline the key components for defense.

Some organizations are very good at knowing what is on their network and collecting adequate logs, pcap, and other records to establish sufficient observabiltiy. Others are good at finding malicious activity where they have established visibility. Some have clear processes in place to address issues and mobilize the business when they are made aware of an issue. Few have the entire spectrum covered and co-integrated. You can see these areas highlighted in common industry breach reports. For example, the Verizon Data Breach Report 2018 contains lines like:

- “Log files and change management systems can give you early warning of a security compromise.” - Referring to Identify and Collect in the Defense lifecycle.

- “In many cases, it’s not even the organization itself that spots the breach—it’s often a third party…” - Aligning with Protect and Detect.

- “Should an attacker get through, you need to be prepared to respond quickly and effectively.” - Mapping to Respond and Recover.

You can review many breach reports and identify where the weakness was in the defense that caused the breach. If you read older reports they are very focused on Confidentiality but as ransomware and data manipulation attacks are becoming more frequent and severe, Integrity and Availability aspects of cyber incursions are more significantly re-entering the dialogue. Very often it is not one thing that failed or lacked controls, but a series of issues that cause the problem. The Equifax 2017 breach is an example where controls failed on multiple levels. The Struts vulnerability that was exploited was not the real failure per se. The visibility to monitor network traffic to and from sensitive systems was not working for 18 months due to an expired certificate. The process of scanning systems failed to identify known vulnerabilities on external facing systems. No detection of the 9,000 queries performed to access sensitive PII data went unnoticed for at least over two months. Inadequate processes and lack of leadership were evident. Architectural failures in the IT environment existed beyond the purview of the security team. These kinds of structural misalignments are all to common and are organizational – not security team – issues to resolve.

Intelligence

Intelligence (intel) is often the least understood but may be replacing Offense as the most talked about category when discussing cyber operations. At the most basic level, intelligence is information that has been collected, analyzed, and disseminated. Many charts will add some additional steps that fit particular use cases, but for clarity and simplicity we are going to keep with the simple three points outlined below for now (Figure 3).

Intel is agnostic of defense or offense and should be used to support both. Intelligence driven operations is a common refrain, but in reality there is a virtuous spiral between Intel, Offense, and Defense in organizations that hit their stride. It is important to remember that signatures, detections, and Indicators of Compromise (IOCs) are just data and information. Intelligence is more than that. Enhancement of data through analysis of context, relationships, sources, and reliability create intelligence. Good intelligence must be tailored for the organization or community for which it is intended.

Common sources of information include:

- Human Intelligence (HUMINT) is comprised of human interactions. This can be anything from other professionals, vendors, law enforcement, social media, etc. This is often how cyber-attacks get tracked back into the physical world.

- Open Source Intelligence (OSINT) is another effective way to collect information. Threat reports, news feeds, social media (some times separated into a separate source), multi-media files, or about anything you can obtain openly and legally. Often OSINT is timelier to support immunization of infrastructure before the attack is seen hitting an organization. The challenge is the information can be inconsistent, often incomplete, and sometimes requires a high level of analysis before utilizing. Many costly threat feed services attempt to minimize incorrect and false information, but these efforts are often completed days after the impact.

- Internal Intelligence is often overlooked and underutilized. Helpdesk tickets, network operations, security operations and other operational groups create a lot of information that is often never revisited after the ticket has been closed (in my experience less than 80%). One reason for this is the information stored in these ticket systems focus on different areas and have different terms and definitions. This makes collection, mapping, and analysis across so many different groups a time-consuming and resource-intensive challenge. These sources are most often utilized forensically after a breach to identify any missing pieces for a timeline reconstruction.

In our next post related to Security Operations Concepts, we will be providing insight into how these three pieces; Defense, Intel, and Offense, can be utilized for organizations.

Resources:

- Wikipedia - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cyberwarfare

- Chaos Monkey - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chaos_Monkey

- Verizon Data Breach Report 2018 - https://www.verizonenterprise.com/resources/reports/rp_DBIR_2018_Report_execsummary_en_xg.pdf

- Equifax 2018 Breach - https://republicans-oversight.house.gov/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/Equifax-Report.pdf